A Colossus Slowed

Published date: 4th Feb 1980, New Delhi

View PDFIndia’s Public Sector Steel Industry

“Our steel industry is gigantic, but still not large enough for our needs. Steel plays a very vital and little understood role in our lives and in our economy. What is steel? How is steel made? Where is it made? Is one steel plant exactly like another? Is the technology we use to make steel modern or antiquated, or is it a combination of both? Now is steel marketed? What sort of people work at producing steel? How do they live? These, and many other questions, are answered in this comprehensive survey, which encompasses six Public Sector steel plants two at Durgapur and one each at Bokaro, Burnpur, Rourkela and Bhilai.”

Ingots moving towards the blooming mill at Bhilai: red-hot ingots that have just been ‘scarfed to remove surface impurities will now be shaped into blooms, long sections that are later shaped into rails.

It is easy to reduce the Indian steel industry to a few facts and statistics. However, there are many stark truths that need to be known the first of these is that India’s steel industry is ‘gigantic’ only by Indian standards: it is by no means large enough to cater to our needs. More than Rs 3,500 crores have been sunk in the public sector steel plants (now called ‘integrated’ steel plants), their work-in-progress, their townships, amenities for employees, and auxiliary industries.

Steel is highly capital-intensive. But investments in the manufacture of steel pay rich dividends in the long run, for steel is the metal spur that makes economies gallop. However, our steel has yet to grow a body around which the nation’s industrial muscle can develop. Today, our crude steel production is only about 15 kg per capita annually, which is abysmally low by international standards (in Japan it is 895 kg, in the USA 621 kg, in the USSR 568 kg, and even in China, 26 kg!)

Obviously, our investment in steel has been insufficient. We have not been able to keep pace with our Mahalanobisian planner’s fond forecasts in the early ’60s that by 2000 AD we would be producing around 100 million tonnes (MT) of steel for an estimated population of 900 million (which works out to 110 kg per capita). During 1979-80, only 8.8 MT of steel will be available. And our steelmakers’ most optimistic predictions project a total availability of 19 MT by 1988-89.

Why? Imbalanced planning would sum it up. India still enjoys major cost advantages in steel production compared to advanced countries. But 32 years after independence we are still debating whether we should plough on towards industrialisation or turn the clock back and be a slow-moving agricultural giant. It is not enough to indulge in harebrained punditry, as one reputed economist-editor recently did, and suggest that it would be more profitable to concentrate on producing food and importing steel. It should be patent that we cannot now shut down our steel plants, throw lakhs of workers out of employment, and halt expansion of our steel production.

Growth Industry

Steel is a ‘growth’ industry as it produces more, domestic demand also grows. And every cog of the national economy is plugged into steel’s hub. Even agriculture, if it is to be hyper-productive, has to employ countless implements made of steel. Steel plays, from sun-up to sun-down, a constant role in our lives. And steel is a ravenously hungry animal it gobbles inputs like iron ore, metallurgical coal, limestone, electricity and technology in ever-increasing quantities. Steel demands a smooth-flowing transportation system its inputs have to arrive in a constant flow, and its products have to move out as constantly.

Steel is a ‘growth’ industry as it produces more, domestic demand also grows. And every cog of the national economy is plugged into steel’s hub. Even agriculture, if it is to be hyper-productive, has to employ countless implements made of steel. Steel plays, from sun-up to sun-down, a constant role in our lives. And steel is a ravenously hungry animal it gobbles inputs like iron ore, metallurgical coal, limestone, electricity and technology in ever-increasing quantities. Steel demands a smooth-flowing transportation system its inputs have to arrive in a constant flow, and its products have to move out as constantly.

Demand for steel rose by over 20 per cent this year. At the same time, power generation touched an all-time low. And in spite of doubling our imports, only 7 per cent more steel will be available over last year.

That there has been a slight increase at all in steel production over last year is a tribute to our steel technologists, who are very good at makeshift improvisations. A joke making the rounds at Bokaro (which is the newest and thus far the biggest of our steel plants, and a ‘symbol of Indo-Soviet cooperation’) has a resident Russian expert throwing up his hands in amazement at how Indian technicians have kept vital running far desired levels. “Bokaro will make every Russian believe in god!” the expert exclaims.

It is difficult for a layman to appreciate the endless jolts our steel plants are subjected to. Key equipment in steel plants like blast furnaces and coke ovens (called ‘thermomechanical equipment) has to be kept in operation round the throughout the Even one day’s shutdown would severely damage sensitive inner linings a blast furnace that ‘trips’ would take at least five months to return to full production. In many ways, the steel technologist being asked to produce steel despite very poor receipts of coking coal, electricity, and raw materials (whose inflow is affected by chaotic rail movement) is like a tailor being asked to sew a shirt without needle and thread.

From bureaucrats to technocrats

India’s first three major steel plants in the public sector, collectively called Hindustan Steel Limited (HSL) at Durgapur, Bhilai and Rourkela, were set up in the late ’50s with capacities of 1 million tonnes (MT) each. The first few years went by in ‘gestation’, and from 1963 onwards, they were stuck by crippling labour unrest. The steel townships’ culture was a new one, and labour leaders quickly found opportunities to exploit the captive labour force of almost 50,000 people, There was also very little coordination with other vital public sectors like the railways and power-generation bodies. HSL’s chairmen were mostly bureaucrats who knew very little about steel, men like S.N. Mazumdar, S.M. Srinagesh, M.S. Rao, all ICS, G.D. Pande, an ex-chairman of the Railway Board, and a short-term deputy chairman, A.N. Banerjee, IAS. It was only in the mid-60s that the first professional head of HSL took over-K.T. Chandy, who was the first chairman of the Food Corporation of India. He was succeeded by Hiten Bhaya, Commercial Director of HSL and a steel technologist. Only after Kumara Mangalam reconstituted the public sector steel plants and formed SAIL in 1973 did things even out-Wadud Khan, who took over from Bhaya as Chairman of SAIL, was also appointed secretary in the ministry of steel and mines. In October 1976, however, Khan was divested of his post in the ministry by the then minister Chandrajit Yadav. Wadud Khan resigned in protest, to be succeeded by R.P. Billimoria, who had been Personnel Director under Khan and had worked previously in Tata Iron and Steel Company at Jamshedpur and in HSL. In June 1978, Billimoria was succeeded by Dr P.L. Agrawal, a metallurgist and lifelong steel-man who had put in many years in Rourkela, Bokaro, and the Alloy Steels Plant.

Durgapur and Rourkela were expanded in the early ’60s from capacities of 1 MT to 1.6 MT and 1.8 MT respectively. Bhilai was expanded from 1 MT to 2.5 MT in 1967. The first stage (1.7 MT) at Bokaro went fully on-stream only around three years ago.

A quick trip around all the steel plants under SAIL can be both an awesome and an educative experience. And that was what this writer and photographer Rakshit set out on in the first week of December. November had been the worst month in recent memory for all the steel plants, for power generation then had plummeted to heart-stopping depths. Durgapur, Burnpur, Bokaro, dep depend on the Damodar Valley Corporation for electricity, and the many occasions on which we crossed the Damodar River showed only a vast expanse of sand. Rourkela had been likewise hit by reduced Orissa, and Bhil generation by the Hirakud grid in Korba grid in Madhya Pradesh. Everywhere, one disquieting fact was brought home – that industry is badly affected as agriculture by Nature’s vagaries.

A Coke evens being ‘pushed’ at Bokaro with insufficient stocks of coal that is of inconsistent quality, the coke ovens thermomechanical life is under strain in every steel plant.

A Coke evens being ‘pushed’ at Bokaro with insufficient stocks of coal that is of inconsistent quality, the coke ovens thermomechanical life is under strain in every steel plant.

B A ladle train moving from the blast furnaces to the steel melting shop at Durgapur: much of the transportation within a steel plant is via plant-owned railway rolling stock.

C The de-gassing plant in operation at the Alloy Steels Plant: after the ASP’s electric arc furnaces turn out steel, it is ‘degassed in order to remove gases that stainless and alloy steels are not supposed to contain.

D The electric-arc furnace at the Alloy Steels Plant: the three huge graphite rods can be seen glowing red-huge hot on top after they have been lifted from the furnace: these rods act as conductors for the furnace’s electric charge.

E The rail mill at Bhilai: red-hot and newly-shaped rails are heading on conveyors towards the final ‘shaping stands’ and the machines that will shear the rails into their final lengths; in the background is the rail mill’s shaping stand.

F A bloom emerging from the blooming stand at Burnpur: these blooms will be shaped into even smaller ‘billets’ that finally are shaped into Burnpur’s ‘merchant products like angles and channels.

G The billet mill at Burnpur: in more modernized plants like Bokaro, such a mill would be highly automated. and the resulting speed would be far greater.

H Cold rolled coils at Rourkela: problems with rail transportation often lead to stockpiling up at the various steel plants.

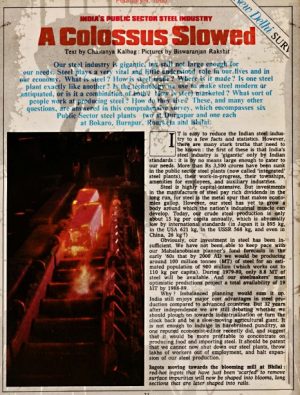

I Rourkela’s fertiliser plant: this naphtha refining plant manufactures calcium ammonium nitrate fertiliser

Durgapur: better and better

Durgapur was set up with British aid, and the major percentage of equipment there is British. Many people feel that feel that Durgapur’s capacity should never have been upped to 1.6 MT-it is actually closer to 1.2 MT. 158 km from Calcutta by rail, the Durgapur Steel Plant (DSP) produces apart from iron and steel products like bars, rods, structurals, sleepers, wheel-and-axle assemblies for the railways, fish-plates, blooms, billets, and pig iron.

The devastating floods in Eastern India in September 1978 hit even Durgapur; moreover, they badly affected output by Coal India Limited. In November 1979, for instance, against an allocation of 210,672 tonnes of coal, DSP received only 152,469 tonnes. This meant that in November only 211 coke ovens could be pushed every day against a target of 275 ovens. Loss of saleable steel production due to electricity curbs in April 1979 was 10,122 tonnes, while in November it soared to an alarming 53,116 tonnes.

Durgapur has three blast furnaces (BFs) with a daily capacity of 1,250 tonnes, and one BF with a daily capacity of 1,500 tonnes. Each BF is charged with roughly 170 tonnes of iron ore, limestone, and coke for each operation. DSP also has nine open hearth furnaces (OHFs), eight of 220-tonne capacities each and one of 120-tonne capacity. Two interesting products at Durgapur are ‘skelps’ (short strips of steel with a maximum width of 9%” used by tube manufacturers) and the wheel and axle assemblies. In the wheel forge section, a 6,000-tonne hydraulic press flattens a half-tonne red-hot bloom into a rough wheel shape. It is then reheated in a heat treatment furnace, centre-punched for axle insertion, and after finishing, sent on to the assembly section. Each set of two wheels and an axle weighs roughly 1.2 tonnes.

The Alloy Steels Plant (ASP) at Durgapur was the first such integrated unit in the country. There are basically between 250 and 300 grades of alloy steels, and stainless steel is one of ASP’s prime products. Even in stainless steel there are various groups. ASP is the only manufacturer of stainless steel for industrial applications, and supplies hot-rolled strips to utensil manufacturers.

During 1978-79, ASP reached 97.3 per cent of capacity utilisation in ingot production, and 81.4 per cent in saleable steel production. Because it is an Electro Metallurgical Plant’, employing electric arc furnaces (EAFs) in its steel melting shop, ASP has been the worst hit in terms of power curbs. Until the end of November 1979, ASP incurred a loss of production of 12,691 tonnes due to power cuts. By staggering different production units’ operations and adjusting the melting and refining cycles of its furnaces, ASP has somehow managed to make do.

ASP has two 50-tonne and one 10-tonne EAFs in its steel melting shop. Important among ASP’s products are armour plate grade steel for defence purposes and forged rounds for seamless tube applications for nuclear fuel complexes. Depending on the grade of alloy or special steel, ASP’s products range in price per tonne from Rs 5,000 to Rs 60,000. This year, because of insufficient power, ASP will certainly suffer a loss, but it has turned in consistent profits over the last five years (although its annual production of saleable steel averages only about 49,000 tonnes, its sale value is very high). Over 3,000 tonnes (worth over Rs 12 crores) of stainless steel— for which demand too has slumped— is lying in ASP’s stockyards.

Priceless alloys

ASP’s equipment is comparatively outdated, so its costs are higher and its yields 40 per cent lower than those abroad. Its steel is also thicker than imported ones and often require further re-rolling. Worst of all, imported steel prices are lower than Indian steel prices. ASP is trying to initiate modernisation schemes where-by steel will be ‘continuously cast— that is, the ingot stage will be wholly eliminated. Unlike other manufacturers of alloy steels in India (Mahindra Ugine, Visvesvaraya Iron & Steel Co. at Bhadravathi in Karnataka, and Bihar Alloys) ASP produces only sheet steel and not bars. The second alloy steels plant in the public sector (at Salem) is due to go on-stream by the end of 1982 and will produce thin gauge cold-rolled sheets.

In a small, heavily-padlocked room in ASP’s steel melting shop which is welded shut every evening, are kept stocks of very expensive ‘ferro-alloys’ like aluminium, ferro-chromium, ferro-manganese, ferro-silica, ferro-molybdenum, which cost anywhere between Rs 50,000 and Rs 75,000 per tonne. Ferro-molybdenum alone now costs around Rs 5 lakhs a tonne!

In ASP’s steel melting shop, the charger adds alloys to the liquid steel bath, which is stirred; 40,000 amps of electricity are then passed through each of three graphite electrodes the bath is then ‘lanced’ with oxygen, and the alloy steel emerges. At ASP, there is also a big de-gassing unit to remove gases from steel required for defence purposes (called ‘spade’ steel). ASP also is the only steel plant to employ electrically fired soaking pits for its distinctive ‘fluted’ ingots. But production at ASP is still affected because this year it has received on an average only 27 per cent of its required power input of 35 MVA.

At Durgapur Steel Plant, General Superintendent Basudev Chakraborty is quite lucid about his hopes, achievements and plans. “Out of 720 hours a month,” he says, “DSP suffered in November almost 650 hours of power restrictions. But we are still trying our best to achieve maximum capacity utilisation. As for labour, DSP had a lot of problems in the ’60s, but now there is a sense of maturity in the posture of militancy. One day in the future even DSP will switch over to LD converters-but our open hearth furnaces are still useful, just like our bullock carts are! We’ve had our share of problems, but there is immense commitment from people who’ve been here for more than 20 years. Durgapur can and will do better and better.

Burnpur’s blast furnaces: commissioned in 1922 and 1924, these are among India’s oldest; after the very expensive plant rehabilitation scheme launched subsequent to the government’s takeover of IISCO in the early ’70s, Burnpur’s equipment has quickly returned to normal, although it is very antiquated still.

IISCO’s re-birth

The Indian Iron and Steel Company at Burnpur (IISCO) and its associated foundry works at Kulti, a few kilometres away, is the second-oldest iron and steel plant in India (IISCO’s first pig iron production was in 1922, while Tata Iron and Steel Company (TISCO) at Jamshedpur produced its first pig iron in 1911. But the precursor to IISCO, the Bengal Iron Works-a foundry plant-had begun operations at Kulti as far back as in 1874. Three blast furnaces (BFs) at Kulti, commissioned in 1920 and 1926, have now been scrapped, while three BFs at Burnpur, commissioned in 1922 and 1924, are still in operation.

When IISCO’s operations touched crisis point in June 1972, its equipment had not been renovated or renewed, and its coke oven batteries and blast furnaces were on the verge of collapse. The government takeover that followed led to a Plant Rehabilitation Scheme to implement the backlog of capital expenditure, and is estimated to cost at least Rs 58 crores by its completion. Today, IISCO is still operating with obsolete technology, mainly Bessemer converters for steel-making; but capacity utilisation, which had risen after the takeover by the government, has again declined to 63 per cent in 1978-79. IISCO has captive collieries at Ramnagore, Chasnalla and Jitpur and their output has been higher than the target during 1978-79. Until November 79, 88,000 tonnes of saleable steel loss in production occurred due to power shortages.

IISCO’s Bessemers are part of the antiquated ‘Duplex’ system of steel-making. IISCO’s SMS (steel melting shop) has three Bessemers and six OHF’s open hearth furnaces) and produces the smallest ingots (weighing about 5.2 tonnes each) in India.

Burnpur’s main products are billets, sheet-bars, blooms, structurals like joists, channels and angles, light 30-lb rails for collieries, and a product peculiar to IISCO and an import substitute-centre-sill ‘Z’ sections for building railway wagon bases. Burnpur is also developing a new colliery arch section to manufacture supports for coal mine roofs.

Kulti’s main product now (from pig iron ingots that are transported there from Burnpur) is centrifugally cast or ‘spun’ pipes-molten iron is poured into a rotating ‘drum’ turning at 900 revolutions per minute and before one’s eyes, the pipe takes shape. Many operations, like rolling the red-hot pipes into the finishing furnace, are done manually. The pipe plant produces 8,000 tonnes of pipes every month, ranging from 700 mm diameters to 450 mm diameters. Kulti also produces ingot moulds for other steel plants. Kulti’s now-defunct BFs last produced iron in 1959.

Although Burnpur is a badly laid-out plant, and consequently crowded, it does not look as grubby as, consequently say, Durgapur Steel Plant-because housekeeping house keeping is much better here. Another peculiarity here is that many workers are third-generation steelmen and are far more attached to their parent plant than workers in other steel plants, where ‘sons of the soil’ policies and newly-trained workers hardly make up for a deep-rooted commitment.

Burnpur’s blast furnaces: Commissioned in 1922 and 1924, these are among India’s oldest; after the very expensive plant rehabilitation scheme launched subsequent to the government’s takeover of IISCO in the early ’70s, Burnpur’s equipment has quickly returned to normal — although it is very antiquated still.

Bokaro Mr Big

From Burnpur to Bokaro by road it takes slightly over 2½ hours. Bokaro, another mammoth example of Indo-Soviet cooperation, has been planned big—everything about it is larger than life. The Steel City, east of the plant, covers about 5,276 acres. Its gardens and plants are carefully tended. There is even an employees’ cooperative housing society with 400 impressive dwellings. But the thing that strikes most first-time visitors is that Bokaro is highly mechanised, has a proportionately lower workforce than other plants, and has many impressive facilities but there is a noticeable lack of warmth. Everything is result-oriented, and every Bokaro employee seems to be over-whelmed by the plant’s size. Bokaro has just completed its expansion from the 1.7 MT stage to the 2.5 MT stage, and work on expansion to the 4 MT stage is already under way.

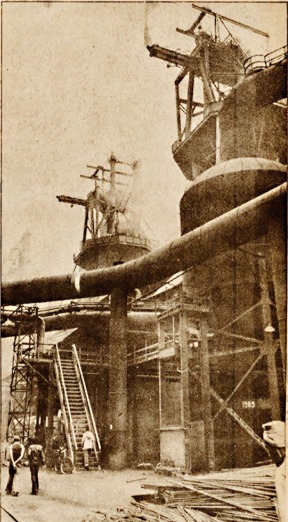

Bokaro’s raw materials handling yard is a huge complex, with three blender-reclaimers and three stackers to process different grades of inputs like coal, iron ore, limestone, etc. All the equipment here is indigenous. Called the ‘Robbin Messiter’ system of raw material handling, blended and sorted raw material is sent via conveyor belts, 22 km in length, to the various plant departments like coke ovens, blast furnaces, etc. 34 per cent of material in Bokaro is conveyor-transported, and this makes for both speed and economy (in other plants inter-shop movement is still via railway tracks).

Bokaro has the tallest coke ovens in India-5 metres high. It has the tallest coke oven chimney too 182 m high. It has the largest blast furnaces-three of 2,640 tonnes per day each. It has a steel melting shop with the largest capacity four LD converters of 100 tonnes capacity each. It has the only on-line-real-time computer-controlled SMS in India. It has a large power station, generating 97 MW. Its BFs make use of as much as 70 per cent sinter, thus utilising waste material like ore fines, and coke dust. Bokaro also has the largest sintering plant in India-two machines, each with a capacity of 11,550 tonnes.

Bokaro’s General Superintendent, Mr M.F. Mehta, is also eloquent about his electricity problems. In April 1979, for instance, against a target of 86,000 tonnes of saleable steel Bokaro produced as much as 79,245 tonnes. But in November, against a target of 115,000 tonnes it produced only 57,861 tonnes. Its ingot production has been much higher, averaging 91 per cent of the target until November. During April-November, the Damodar Valley Corporation imposed restrictions for approximately 5,076 hours, and Bokaro’s system remained ‘isolated’ on 437 occasions for 1,055 hours. Ingot steel therefore could not be processed in the slabbing mill, and semi-finished steel could not be further processed into finished steel in the hot strip mill and the cold rolling mills.

Although Bokaro is situated in the heart of the coal belt, barely 30 miles from Dhanbad, power restrictions at collieries too have hit its coal supplies. For a high-technology plant like Bokaro this can be disastrous, for its BFs and coke ovens suffer if coal blends change and if oven-pushing is reduced.

Bokaro’s hot strip mill is a colossal 1.25 km long structure, and watching the red-hot slabs being rolled through seven stands’ of finishing rollers at a speed of 17 metres per second is unforgettable. At the end of the run the strips are coiled in a three-machine section in lengths exceeding 1 km. Everything is automated, and technicians monitor operations from an air-conditioned ‘pulpit’ alongside the mill. Later, after being pickled’ in sulphuric acid, these hot-rolled coils are further rolled in four cold-rolling ‘tandem’ stands into strips varying in thickness between 0.4 and 2 mm. The cold-rolled coils are then ‘annealed’ in closed ovens in a nitrogen protective gas atmosphere to refine their grain structure and obtain the required physical properties.

Bokaro’s raw-material handling yard: This gigantic ‘stacker’ piles raw materials in heaps, as on the left, after they have been sorted and blended alongside; this method of raw-material processing, which exists elsewhere only in Durgapur, vastly improves steel plant operations.

Bokaro’s raw-material handling yard: This gigantic ‘stacker’ piles raw materials in heaps, as on the left, after they have been sorted and blended alongside; this method of raw-material processing, which exists elsewhere only in Durgapur, vastly improves steel plant operations.

Rourkela: from CAN to cows

From Bokaro we return to Calcutta by train, and leave again for Rourkela by the comfortable Rourkela Express, an overnight journey. Rourkela was commissioned in the late ’50s with collaboration from West Germany (Krupp and Demag). It was the earliest in India to use the LD Converter technology in its steel-making. Rourkela Steel teel Plant (RSP) is also the only plant to have its own fertilizer unit, which utilises nitrogen and hydrogen from the steel plant to produce 459,000 tonnes of calcium ammonium nitrate (CAN) fertilizer with 25 per cent nitrogen content.

RSP has three LD converters of 50 tonnes capacity each, and two of 60 tonnes capacity each. It also has four open-hearth furnaces (OHFs) which produces steel for RSP’s pipe plant and plate mills. Its Finished steel mills include a heavy plate mill (for defence applications), a hot strip mill, a cold rolling mill, an electrolytic finning line (ETL), two coil galvanizing lines, one electrical resistance welding (ERW) pipe plant, and one spiral weld pipe plant.

Commissioned in June 1976, the spiral weld pipe plant produced 804 km of pipelines for the Mathura Refinery well within its deadline of 36 months, and this innovation saved the country Rs 49 crores in foreign exchange (the first few hundred kilometres of pipeline at Mathura had been imported). At the ETL, cold-rolled sheets are tinned in huge coils, cut into sheets later and used by can manufacturers. Depending upon the specification, tinning is done anywhere between 5.6 grams and 22.4 grams per square metre of cold-rolled steel. In the galvanising plant, cold-rolled steel is coated with zinc varying between 375 grams and 700 grams per square metre, then sheared and piled in 2.5 m-long sheets.

Electrical-resistance welded pipes are another Rourkela speciality. Here, hot-rolled coils are fed into levellers, blasted with tiny cast-iron shots to remove scales, shaped into circular elongations by ball-rollers in eight tandem stands, and then seam-welded over a huge copper-coated wheel. These pipes are used for irrigation, and range in outer diameter from 8%” to 18″. Spiral welded pipes are also a Rourkela innovation. Ranging in outer diameter from 14″ to 64″, these hot-rolled sheets are submerged-arc welded, tested with X-rays and ultrasonics for blemishes, and then cut into required lengths.

Among expansion plants at RSP are included a silicon steel plants for specialised applications, and a cement plant (again a first) that will utilise slag from both RSP and Bhilai.

Rourkela and Bhilai have not been so badly affected by power cuts as Durgapur, Burnpur and Bokaro have been, yet RSP has already lost this year saleable steel production amounting to 70,387 tonnes. Nonetheless, RSP, which made consistent profits ever since 1974 and till 1978 has turned in a cumulative profit since inception of Rs 72.02 crores, seems prepared to solve its problems. Dr N.S. Datar, the Managing Director of RSP, says that his plant’s major attempt in the near future will be to keep the plant healthy by regular revamping and maintenance internally. In May 1980, he anticipates that the hot strip mill will be shut down for 45 days in order to finalise implementation of a Rs 30-crore modernisation scheme. New markets in the Far East and the Middle East for spiral weld pipes are being explored, and nationally too this plant ought to have a good market. Dr Datar feels spiral weld pipes could also be advantageously used as storage ‘silos’ in villages for grain. RSP, says Dr Datar, has over 62,000 tonnes of steel lying in its stockyards, against an ideal level of 32,000 tonnes. “This is mainly due to very bad rail movement,” he says. “30 to 40 per cent of the wagons that come to RSP are ‘sick’, inoperative.” The cement plant at RSP, which only requires approval by the Public Investments Board (PIB) now, will use advanced precalcinator technology and produce as much as P 3,000 tonnes of cement a day, and will be the biggest cement plant in India-with an annual capacity of 1.89 MT.

Under Dr Datar’s leadership, RSP has also been participating in an impressive ‘peripheral development’ programme name in 63 villages around the plant. RSP builds schools in these villages, sinks wells, and is arranging for bank loans so that each villager can buy two Jersey cows. Milk from this cooperative will be purchased in bulk by RSP itself, which will also provide veterinary services and arrange for fodder at cheaper rates. There are 10,000 ‘displaced persons’ (tribals) around Rourkela, and 70 per cent of them have found employment in the steel plant.

Rourkela’s galvanising line: the only one of its kind among the public-sector steel plants. Here, cold-rolled coils are coated with zinc to produce galvanized sheets:-the galvanised sheet is rising from the ‘zinc bath’ into which the worker is putting fresh ingots of zinc.

Rourkela’s galvanising line: the only one of its kind among the public-sector steel plants. Here, cold-rolled coils are coated with zinc to produce galvanized sheets:-the galvanised sheet is rising from the ‘zinc bath’ into which the worker is putting fresh ingots of zinc.

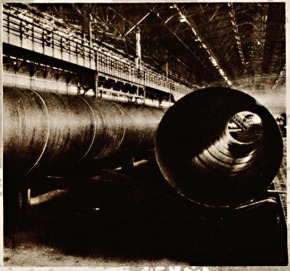

Rourkela’s spiral-weld pipes: the spiral welding lines can clearly be discerned along these pipes; Rourkela delivered these pipes in good time to the Mathura Refinery and saved the country many crores in foreign exchange—they were earlier imported.

Bhilai: a growth centre

Bhilai is also a night’s train journey away from Rourkela. Bhilai Steel Plant (BSP) which was expanded to the 2.5 MT capacity stage in 1967, is the largest operating steel plant in India (although Bokaro will soon match it in production and is already larger in size). Another and an even earlier symbol of Indo-Soviet collaboration, BSP too has made consistent profits over the last six years, but is as badly affected by power curtailment and insufficient inflow of raw materials as the other plants are.

In an unusually planned manner, Bhilai’s expansion to the 4 MT stage is coming up alongside the present plant in such a way that operations at the plant are not affected at all. In this stage, Bhilai too will acquire three LD converters, each of 120 tonnes capacity. A continuous-casting scheme is also under consideration.

Bhilai has been receiving only 75 per cent of its actual power requirements from the Madhya Pradesh State Electricity Board’s Korba hydro-electric project. In order to augment its coal stocks (which are also at an alarmingly low level), BSP has now begun to use coal from the Western Coalfields which is not as good as the Bihar-grade coal.

BSP too has sinter utilisation capacity of 60 per cent in its blast furnaces-it has six BFs, the largest number in one plant. The LD converters in the new steel melting shop (SMS) in the 4 MT stage are expected to go on-stream by late 1981. Each of BSP’s ten open hearth furnaces takes 12-13 hours for each heat. In the blooming mill, each ingot passes through an average of 11 passes through the main stand before the bloom emerges. Blooms are sent directly to the rail and structural mill, and to the billet mill for further rolling into billets that ultimately go to the merchant mills.

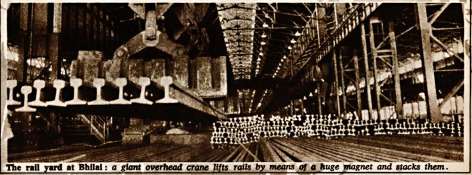

Bhilai’s characteristic products are rails—it is designed to produce 7.5 lakh tonnes of rails and heavy structurals every year. Although TISCO also produces rails, Bhilai far surpasses it in aggregate production. In the merchant mill, billets are shaped into beams, channels, angles, flats and bars—with an annual capacity of 500,000 tonnes. The wire-rod mill is designed to turn out 4 lakhs tonnes of wire-rod coil each year. Here, 80 mm square 12 metre long billets, each weighing about 600 kg, are first charged in a reheating furnace and then rolled through a four-stand continuous, wire rod mill which at the finishing stage reaches a speed of 30 metres per second.

Mr S. R. Jain, BSP’s Managing Director, says that although close liaison has been maintained with the MPSEB, all finishing mills are shut down for an average of four hours every evening. During 1979-80 BSP anti-cipates a saleable steel production loss of 45,000 tonnes. As for coal, Mr Jain says that this year alone BSP had to resort to blending different grades (prime, medium and blendable) of coal on seven occasions. “In the past we never had to do this more than once a year,” he says. Imported coking coal has saved the situation to a large extent, but for how long, asks Mr Jain. When BSP’s continuous-casting facility comes into operation, he anticipates a dramatically improved yield from the blooming and slabbing mills. Prime products then will be heavy plates for shipbuilding and other heavy industries.

Over 7 lakh cubic metres of concrete have so far been poured into Bhilai’s expansion scheme. The daily consumption of cement alone works out to about 300 tonnes. With Soviet help and MECON’s consultancy Bhilai is gradually modernising all processes in its 2.5 MT stage. Like Rourkela, Bhilai to has a peripheral development programme. 35 neighbouring industries have recently been given the status of ‘ancillaries’, and BSP’s annual orders to them total over Rs 2 crores. These ancillaries supplement in-plant fabrication and maintenance facilities. 30 villages have been adopted by BSP so far, and 40 tubewells have been sunk. During 1979-80 the community development department will spend almost Rs 7 lakhs. Among R&D schemes, Mr Jain lists coal-dust injection experiments in the BFs to reduce coke rate which will begin by 1981. One OHF is being converted into twin baths, so that the oxygen consumption is more. The billet mill is to be computerised to reduce rejections. Rs 30 crores are to be spent on modernising the Dalli mines, where BSP gets its iron ore from.

It would, of course, be impossible to list in minute detail the sights and sounds that one is exposed to in the steel plants and their townships, and to describe the technological details in each plant. One trip covering all the plants in a short period of time is also not enough to absorb all of steel’s angles. But steel is a fascinating medium, and any visitor with a minimal interest in industry will soon ingest volumes of information on steel-making, and converse in the steel man’s lingo stacking, blending, pushing, ramming, quenching, charging, teeming, tapping, rolling, and so on. For many of us, steel-making has at best been some flow-charts in school. No flow chart can represent the breathtaking expanse, the heat, the noise, the magic of the liquid steel pouring out. It is when peering into a ladle filled with molten steel and watching the stream of golden-red liquid pour out that one comes closest to an appreciation of how exactly steel gives our nation its sinews.

We have many years to go before we reach a high-productivity level in steel, before our infrastructural facilities are pluperfect, before we enter the real industrial boom. But watching men in steel plant after steel plant at work, seeing their pride in their task, listening to them describe the machines they live with in patient detail-that, in itself, is a message of hope.

The Story Of Steel

STEEL production depends on an uninterrupted inflow of inputs like coking coal, electricity, water, and oxygen, and raw material like iron ore, limestone, manganese ore, dolomite, and scrap iron. Raw coking coal (also called metallurgical coal) is unloaded from railway wagons by tipplers that turn and empty the wagons, and stored in either bunkers or silos. From here coal is sent to a hammer mill where it is powdered to ” fineness, and then onwards to the coke ovens. Each steel plant has ‘batteries’ of coke ovens (Bokaro, for example, has 4 batteries of 69 ovens each). A coke oven is an elongated iron structure, between 4 and 5 metres in height, lined inside with refractory material. Each oven is ‘charged’ (filled) with the crushed coal and after the oven is shut the coal is heated in the absence of air. This process (called destructive distillation of coal) drives out volatile matter like coke-oven gas (which has a high calorific value and is good for heating purposes elsewhere in the plant) and carbonised coal, called ‘coke’, results. The charging time for a coke oven varies from plant to plant (at Durgapur for instance the coking time is more than 20 hours, while at Bokaro it is 16 hours). Coke oven gas is further distilled to obtain by-products like tar, naphthalene, PC (pitch-creosote) mixture, xylene, benzeine, ammonium sulphate, etc.

From the coke ovens, coke is sent to the blast furnaces. The blast furnace is charged, apart from coke, with iron ore (also crushed to blast-furnace fineness), limestone, and dolomite. In latter-day plants, blast furnaces (BFs) are also charged with ‘sinter’. Sinter is a hard, porous agglomerate produced by the fusion of metallurgical wastes like the finer fractions of iron ore, limestone, coke, flue dust and mill scale on a travelling grate with a down-ward draft. Besides utilising such otherwise useless wastes, sinter helps reduce the consumption of coke and flux in the BF and improves BF operation and the quality of iron. Bokaro has BFs designed to utilize sinter up to 70 per cent of total inputs.

In the BF, iron present in the form of oxides in the ores is extracted by the inter-action of ore, coke and limestone at high temperatures (a BF is heated by hot air heated in huge ‘stoves’ that are in turn fuel led by coke-oven gas). Limestone and dolomite combine with the impurities in the ore to form a ‘slag’, which floats on the surface of the ‘hot metal’ in the BF. Both slag and metal are ‘tapped’ (allowed to flow out from the BF) at regular intervals.

The steel-melting shop

From, the BFs, hot metal goes to the steel melting shop (SMS), also called the ‘mother’ shop, for this is where steel is actually produced. Different steel plants have different types of steel-making equipment. Burnpur still uses the now-antiquated Bessemer converters in combination with open-hearth furnaces (OHFs). Durgapur and Bhilai use only OHFs. Bokaro uses only the most advanced LD converters (named after two Austrian towns. Linz and Donowitz, where this improvement on the Bessemer was perfected in the late ’50s). Both at Vishakhapatnam (where the biggest-ever steel plant in the country is scheduled to go on-stream in the mid-80s) and in Bhilai’s expansion from the 2.5 MT to the 4 MT stage, only LD converters will be used.

Whichever technique is used in the SMS, the process is essentially the same hot metal comes from the BFs to ‘mixers’ where it is again heated and then to the SMS, where scrap metal, further quantities of coke, limestone, and dolomite is added. In the OHFs, and in the LD converters hot metal is ‘lanced’ with oxygen that is water-cooled. The amount of oxygen used varies from 55 cubic metres (m³) in OHFs to 60 m³ in the LD converters. The oxygen combines with the carbon in the hot metal to produce carbon monoxide (CO) and carbon dioxide (CO₂), further slag, and finally, liquid steel.

Liquid steel is ‘tapped’ (i.e. poured out from the furnace) into huge bucket-like ‘ladles’ secured on either side by ‘tuyeres’ (a tong-like contraption) From here the ladles of molten steel travel by huge overhead crane systems to the ‘teeming’ yard where steel is poured through a nozzle at the bottom of the ladle into ingot moulds. The tap-to-tap time in an OHF can be as much as 10 hours, while in LD converters it is usually around an hour.

The ingots moulds are then transported to a ‘stripper bay’ where they are removed from the ingots by means of hooks on either side of each mould, leaving the glowing, red-hot ingot. Each steel plant also diverts some hot metal from its BFs to another mill where it is cast into pig iron (used) by foundries etc). Slag from both the BFs and SMS furnaces is allowed to cool, ‘granulated’ (crushed) in a separate plant, and sold to cement manufacturers, for whom it is an important raw material.

When we refer to the ‘capacity of a steel plant, we are actually referring to the capacity of its steel melting shop. Durgapur’s capacity at present is 1.6 MT, the Alloy Steels Plant’s is 100,000 tonnes, Rourkela’s is 1.8 MT, Bhilai’s is 2.5 MT, and Bokaro’s first stage capacity is 1.7 MT, while Burnpur’s capacity is 1 MT.

Finishing mills

Nowadays, because all mills in our steel plants are operating far below their capacities, ingots are piling up. Each ingot can vary in weight. In Durgapur one ingot weighs 8 tonnes, while at Bokaro it can weigh as much as 20 tonnes. After being ‘soaked’ in fuel-fired or electrically-fired ‘soaking’ pits in order to remove surface impurities and ‘scales’, the ingot is then sent on to the plant’s ‘basic’ mill where it is first re-heated in a furnace and then rolled into either blooms (long sections, square in cross-section, of red-hot steel) or billets (smaller versions of blooms), or slabs (red-hot steel lengths, rectangular in cross-section).

Depending on what the plant’s final products are, the blooms, billets, or slabs are then sent on to the hot strip mill (as at Bokaro where steel is rolled into sheets varying in thickness from 1.5 to 10 mm) or the cold rolling mill (where hot-rolled strips are further rolled into sheets, coils, tin plates and galvanised sheets) or the rail and structural mill (as at Bhilai, where blooms are shaped into rails etc) or the merchant mill (where billets are shaped into rods, rounds, angles, flats, channels, beams, or wire rods). Unlike BFs and the SMS, a steel plant’s mills operate totally on electricity, which is why this year’s power shortage has led to greatly reduced production of saleable (i.e. shaped) steel.

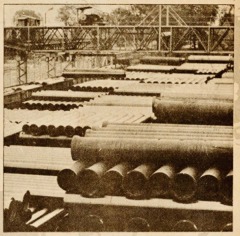

Spun pipes stacked at Kulti: as in other steel plants, IISCO is also facing movement problems with regard to its products.

THE MARKETING OF STEEL

Beset With Pitfalls

THE total quantum of saleable steel available in the country is represented by the total production of the steel plants and the mini steel plants plus imports. There has been an increase this year alone of 7 percent in the availability of saleable steel products. Yet, there is a shortage in the market, and demand has been steadily rising over the last two and a half years due mainly to buoyancy in industrial activity.

Right from 1959, sales of all public sector steel plants’ products was centralised under the Central Sales & Marketing Organisation. Today, with the formation of SAIL, the CSMO’s operations vis-a-vis domestic sales, imports, and exports have increased manifold. At a lengthy discussion in his headquarters in Calcutta, Mr H.R.S. Rao, the CSMO’s chief executive, and his general managers for export and import and transport and shipping, Mr C.S. Mohan and Mr G. Ramachandran, described the organization’s operations and problems in detail.

The CSMO was planning to introduce around 10.3 million tonnes (MT) of steel into the market during 1979-80. Production from the integrated public-sector steel plants was expected to be roughly 7.4 MT. But due to a crippling power shortage from September 1979 onwards, shortfalls in coal receipts and uncoordinated rail movement, this figure will most probably come down to only 6 MT by 31 March 1980. Around 1.4 MT of steel is likely to be imported during the current year, and with the addition of mini steel plants’ production, the total available steel during 1979-80 is likely to be only 8.8 MT.

The government, says Mr Rao, “wisely” decided to import substantial quantities of coal this year and that helped offset to some extent the steep drop in coal production in the country. But the major problem faced by the marketing people is rail movement.

Prior to 1974, the bulk of steel was despatched directly to SAIL’s customers from its steel plants. During the Emergency, however, both demand for and production of steel rose sharply (we even ex-ported large quantities of steel at rates well below our market prices to clear stocks during 1975-77) and the railways switched over to bulk transportation of steel in ‘rakeloads’ (a rake is a full complement of around 30 ‘boxes’ or wagons). Until then, only foodgrains had been transported in rakeloads.

Stockpiling woes

But after 1977-78, both production and demand for steel began to drop, due mainly to low coal production (caused both by disasters like the floods in W. Bengal last year and the Chasnalla tragedy in 1976) and poor power generation. Wagon availability from the railways has also gone down due to increased goods traffic and rising wagon sickness (incapacitation of wagons). But the railways have, pleading optimum utilisation of rakes and directional economies, been insisting on rakeloads of steel products. This has caused tremendous problems for SAIL, for it has been forced to stockpile big quantities of steel at its stockyards, and to divert unnecessarily extra quantities of steel to consumers with smaller requirements.

One major problem is that SAIL markets many different types of steel (like bars, billets, sheets, rods, angles, channels, rails, coils, wires, plates etc) and these are ‘rolled’ in the mills in various plants at varying intervals-because of power shortages, certain mill sections have to be rolled, for instance, only once in two months. It is not possible for SAIL to pile huge quantities of saleable steel at the plants themselves, for they are already choked with huge ingot stocks which have not yet been rolled. There-fore, it is often impossible to despatch rakeloads of a particular steel product.

This gives rise to ridiculous situations. Recently for example, Sikkim ordered 1,000 tonnes of galvanised sheets. But because the railways insisted on transporting an entire rakeload of galvanised sheets (which amounted in this case to 1,700 tonnes) Sikkim is now saddled with 700 extra tonnes of unrequired galvanised sheets! Some other consumer, obviously, has to suffer because of this tied-up stock.

Sectoral priorities

60 per cent of steel produced by the integrated steel plants in any case is reserved for important sectors like the railways themselves, defence establishments, electricity and water irrigation boards nationwide, small-scale industrial corporations, the Engineering Export Promotion Council (EEPC), various public sector undertakings, and SAIL’s own rural distribution outlets. At no point of time does SAIL possess more than 15 days steel production’s storage capacity. If there are route restrictions and non-availability of wagons of the types SAIL re-quires (as many as five different types of wagons are needed for different types of steel products), sectoral and regional priorities get disturbed.

Consumers are also affected adversely because they cannot utilise certain types of steel SAIL has supplied— they cannot obtain ‘matching’ steel products, again due to movement problems. These ‘diversified’ consumers include engineering and structural fabrication industries.

Even for imported special steels required by consumers in specific quantities, the railways refuse to move loads less than 57 tonnes, even if a consumer who needs, say, 35 tonnes, offers to pay full freight. Optimization of wagonloads is the railways’ slogan. SAIL has 175,000 tonnes of imported steel lying at different ports right now.

All steel prices in India are set by the Joint Plant Committee, whose chairman is the Iron and Steel Controller (who operates from the ministry for steel and mines). There are no price controls on mini steel plants’ products and on products turned out by re-rollers, i.e. small manufacturers who further shape saleable steel into market specifications. SAIL’s marketing is essentially consumer oriented. Very little steel is sold to middlemen traders. Today, the big and established steel traders countrywide obtain only about 2 per cent of total steel production. These traders have always in the past rescued producers when they have faced problems in disposal of steel by buying steel, stocking it, and gradually filling the market. There is still some artificial inflation of steel prices in the market because some so-called consumers (who have to register themselves with the Iron and Steel Controller) re-sell their stocks, creating ‘leaks’.

In sum, Rao is optimistic about solutions to these problems. The railways will sooner or later have to recognise that steel is a heterogeneous product that would at best require multi-point unidirectional movement, unlike homogeneous products like foodgrains, fertilisers, or coal that lend them-selves to bulk rakeload movement.

COMPUTERISING STEELMAKING

Bokaro Leads The Way

All over the world, the computer is an indispensable part of advanced steel technology. In India, however, Bokaro is the first and so far the only plant to have installed a computer in its steel melting shop (SMS). Soon, inventory control and production planning too at Bokaro will be computerised. The new LD converters in Bhilai’s expansion will similarly be computerised, as will the LDs in the Vishakhapatnam plant.

In a clean, glass-panelled operations centre perched above Bokaro’s SMS sits an IBM 1800 computer. In a steel plant where expertise has either been Russian or Russian-trained, the computer is run, strangely, by US-returned systems manager R.N. Dutta. Dutta worked for many years in the US Steel Corporation’s Gary, Indiana, works. He is justifiably proud of his IBM 1800, and explains its usefulness in great detail.

The LD Process, Dutta says, is extremely complex and fast. Each ‘heat cycle’ takes not more than an hour, and various reactions are undergone as the iron becomes steel. Oxygen has to be blown (or ‘charged’) into the LD converter for a specified period of time (usually a little less than a half-hour). The oxygen reduces the carbon in the hot metal to proportions ranging from 0.08 per cent to 0.05 percent, depending on the stipulated grade of steel. To ensure this, exact quantities and volumes of various inputs have to be ‘charged’ into the LD at a temperature averaging 1620 degrees Centigrade. To facilitate this, Dutta’s IBM 1800 has been programmed with a ‘thermochemical model, a plain image of the steelmaking process expressed in thermal or chemical equations. Data from, say, 150 ‘heats’ is fed in, and an average or ‘mode’ arrived at. Whenever it is posed a problem, the computer ‘invokes’ this mode.

J Blast furnaces at Bokaro: on the right is the Damodar River; Bokaro’s blast furnaces are the largest, right now, in India.

K Slag being ‘tapped’ at Burnpur: impurities that float on top when iron ore is melted and later on when steel is made, slag is used as an essential input by cement plants.

L One of Burnpur’s Bessemer converters: the oldest system of steelmaking still exists in IISCO at Burnpur; the modern LD converter system is basically an improvement on the Bessemer process.

M The hot strip mill at Rourkela: here, ingots are first shaped into ‘slabs’ and then rolled into strips; at the end of the run, they are coiled in huge stands, and if finer thicknesses are required, they are sent on to the cold rolling mill for further rolling.

N The centrifugally cast pipe plant at Kulti: once the oldest steel plant in India, Kulti is now a forging plant. This ‘spun pipe’ has just been propelled towards a finishing furnace towards the left by the worker in the picture.

In the ‘pulpit’ of the SMS’s mixer shop, an operator sits at a keyboard printer that is plugged into the computer. Depending on the end grade of steel required, the percentage of carbon required, and the tonnage required, the mixer shop operator is told by the computer exactly how much scrap, hot metal, limestone, lime, bauxite, and ore for coolant he is to ‘mix’ for the subsequent LD charging. A lower quantity of hot metal, says Dutta, might result in a ‘cold heat’, i.e., an abortive heat. Bokaro is the only industrial plant in India, he points out, where a computer controls on-line, real-time process, i.e., it monitors each process as and when it takes place round the clock.

DR P. L. AGRAWAL

DR P. L. AGRAWAL

We Have A Motivated But Frustrated Workforce’

DR P.L. Agrawal, chairman of the Steel Authority of India Limited (SAIL), is an internationally-reputed metallurgist. He is president of the Indian Institute of Metals for 1979-80, and also a director of the International Iron and Steel Institute, Brussels. A pleasant and articulate person, Dr Agrawal met me in his office suite at SAIL’s corporate headquarters in Delhi.

To the often-repeated theory that steel, as a capital-intensive industry, should not be expanded any longer and that the country ought to concentrate on agriculture, Dr Agrawal says: “This year we will be importing almost 1.9 million tonnes (MT) of steel. Even at Rs 3,000 per tonne-which incidentally is a higher price than that of steel produced in India-our total bill for steel imports would easily cross Rs 500 crores during 1979-80. The demand for steel in India is rising every year this year alone it is 12 to 15 per cent more than last year’s. And with our best efforts we have not been able to keep pace with what the Planning Commission envisages for the steel industry-a growth rate of 6 per cent annually. This year our capacity- which is not the same as our production-nationally, including mini-steel plants capacity, would be somewhere around 14 MT. The Planning Commission envisages a capacity of 44 to 45 MT by the end of this century. Steel has to keep expanding! How long can our government go on subsidising steel imports so that their prices match domestic rates? Even if we achieve a growth rate of 6 per cent per annum in steel capacity we will still have to import. In any case, I feel that by the late ’80s we will have no money left to buy anything but oil. The rural-economy argument, therefore, is fallacious.”

Per-tonne costs

India’s investment in steel in any case is going up every year, says Dr Agrawal. But, he says, we will suffer because not enough investment was made in steel in the ’50s, when the need was greater. “The per-tonne cost-total investment in a greenfield plant divided by its tonnage of a steel plant in the 50s was between Rs 1,500 and Rs 1,900. At Bokaro, which was largely built in the ’70s, the per-tonne cost went up to almost Rs 3,000. Bokaro’s second-stage per-tonne cost alone will be almost Rs 4,500. And for Vizag, our estimates are that the plant will cost us about Rs 10,000 per tonne to put up!”

Increasingly, steel capacity worldwide is shifting to developing countries, says Dr Agrawal, because their economies are more export-oriented. “By the mid-80s there will definitely be a steel famine,” he says, “and a poor country like India will have to pay much more for its imported steel than it is paying now.”

Input-wise, SAIL’s chairman is not at all happy. “You can’t operate a steel plant with two or three days’ stock of coal,” he says. “This goes for other key inputs too. So we are producing much less than we can. Internally and organisationally steel is quite strong today; we have a motivated and at the same time frustrated workforce.”

Dr Agrawal was the first general superintendent of Bokaro in 1970, and on his insistence the then Bokaro chairman Mantosh Sondhi (who is now secretary in the ministry of steel) called Damodar Valley Corporation officials for a meeting to decide whether power supplies in the ’70s would be sufficient. “DVC then kept repeating that there would be more than enough power,” recalls Agrawal. “In 1973, we went to the government with proposals for additional power-generation capacities at Durgapur, Rourkela and Bokaro. Once again we were told that there would be enough power, why invest in private capacity? Now look at the situation! No power anywhere! Finally, we have now approved power-plant schemes for Durgapur and Bokaro, which will obviously cost much more to install than they would have in the early ’70s, but not for Rourkela, because the Orissa government still insists that they have enough power. The problem is that more than 30 per cent of the Orissa State Electricity Board’s re-venue is generated from the Rourkela steel plant alone. All state electricity boards treat steel plants’ loads like golden eggs, and refuse to part with them. But because steel plants are bulk consumers, these same electricity boards can quietly cut supply by pleading that cutting supply for many small consumers would be bothersome!”