Fali S Nariman – PIL is not an indictment of the failure of the system

Published date: 2008, Aug 2008, Halsbury's Law

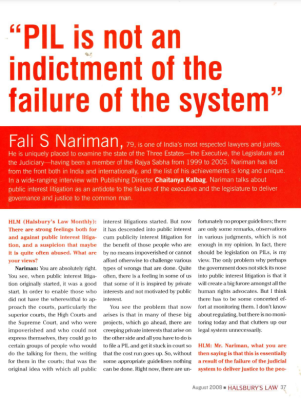

View PDFFali S Nariman, 79, is one of India’s most respected lawyers and jurists. He is uniquely placed to examine the state of the Three Estates — the Executive, the Legislature and the Judiciary — having been a member of the Rajya Sabha from 1999 to 2005. Nariman has led from the front both in India and internationally, and the list of his achievements is long and unique.

In a wide-ranging interview with Publishing Director Chaitanya Kalbag, Nariman talks about public interest litigation as an antidote to the failure of the executive and the legislature to deliver governance and justice to the common man.

HLM (Halsbury’s Law Monthly): There are strong feelings both for and against public interest litigation, and a suspicion that maybe it is quite often abused. What are your views?

Nariman: You are absolutely right. You see, when public interest litigation originally started, it was a good start. In order to enable those who did not have the wherewithal to approach the courts, particularly the superior courts, the High Courts and the Supreme Court, and who were impoverished and who could not express themselves, they could go to certain groups of people who would do the talking for then, the writing for them in the courts; that was the original idea with which all public interest litigations started. But now it has descended into public interest cum publicity interest litigation for the benefit of those people who are by no means impoverished or cannot afford otherwise to challenge various types of wrongs that are done. Quite often, there is a feeling in some of us that some of it is inspired by private interests and not motivated by public interest.

You see the problem that now arises is that in many of these big projects, which go ahead, there are creeping private interests that arise on the other side and all you have to do is to file a PIL, and get it stuck in court so that the cost run goes up. So, without some appropriate guidelines nothing can be done. Right now, there are unfortunately no proper guidelines; there are only some remarks, observations in various judgments, which is not enough in my opinion. In fact, there should be legislation on PILs, is my view. The only problem why perhaps the government does not stick its nose into public interest litigation is that it will create a big furore amongst all the human rights advocates. But I think there has to be some concerted effort at monitoring them. I don’t know about regulating, but there is no monitoring today and that clutters up our legal system unnecessarily.

HLM: Mr. Nariman, what you are then saying is that this is essentially a result of the failure of the judicial system to deliver justice to the people who are really the needy ones.

Nariman: Yes, but you see the desire is there but the mechanics of it somehow does not work out because each judge has his own idea on how PILs should proceed.

HLM: But PILs in themselves are an indictment of the failure of the system.

Nariman: I don’t think that it is a failure of the system. It is only giving another sort of an avenue for people who would otherwise not be able to, that’s all.

HLM: Do you think that there should be a screening mechanism?

Nariman: That is what we have suggested but that never saw the light of day.

HLM: Do you think that the concept of PILs is unique to India?

Nariman: It is exists in many countries. In fact nowadays, all over the world there is a realisation that justice has to reach the poor and the needy. Especially with globalisation, there are large sections of society which feel left out and want to know what they can do to get going. And there are a lot of pro bono lawyers in America particularly; there are big law firms that set aside a big section of their firm for pro bono work only, and they do it rather well.

HLM: Is there enough pro bono work going on in India?

Nariman: Oh yes, tremendous. There are a lot of NGOs which are doing excellent pro bono work….But if you start organising these things and making them into companies or firms then it becomes another institution. It is best left to individuals, in my view, to champion the cause of something which they consider to be important; it’s always good that way.

HLM: Can you recall one or two examples when PILs have done a tremendous amount of good.

Nariman: Oh yes, the PILs have done well in exposing all these scams. A large number of scams are being exposed nowadays in the judiciary; for instance the recent Ghaziabad District Bar Association scam. In such cases, it is said that the CBI should take up cases instead of the police, and in that sort of atmosphere the courts call for the papers and considers the matter and decides what to do. In the old days, it used to be said that if the police has started an investigation, then nobody can interfere; but today, nobody trusts the police. In fact, nobody trusts anybody. The politicians don’t trust the police, the lawyers don’t trust the judges and the judges don’t trust the police. So, it is a vicious sort of a circle.

HLM: That is a very interesting point. So a lot of it stems from a lack of trust.

Nariman: Yes, and the lack of trust is amongst the institutions which are supposed to instill the trust and confidence in the community. That is a very big problem that we are facing in our judicial system today but hope-fully we should be able to come out of it because there has to be some vision. In my view, you cannot achieve something unless you have the vision to do it. The Supreme Court can itself do a great deal if it wants to because whatever it says on the Bench is law, and that makes a lot of difference.

We had a project many years. ago, when I appeared for one of the political parties against a public interest litigation. Ultimately, after several years, it was dismissed by the Supreme Court: it was a very good irrigation project in the south, near Bangalore. But unfortunately, by the time the judgment came, the foreign collaborator was no longer willing to continue. So he pulled out and it was a great loss to the country; it was a big Hong Kong based company which came. These things happen, you know.

HLM: What is your opinion on the huge backlog of cases that exist in the courts? In a way PILs seem to shortcut the process to quite an extent.

Nariman: I don’t think so. They get into the same queue.

HLM: I thought they do attract more attention.

Nariman: The public attention; the media attention. But then the media has something else to pick on, so they forget the real case.

I’ve tried to fathom how to get out of this three tier system. We have a three-tier system in India, sometimes four. That is to say it goes from the lower court; High Court at two stages, then to the Supreme Court. So, it is a necessarily slow process but it gets unnecessarily longer because people don’t speed it up. In England, Lord Woolf has recently introduced a certain set of re-forms that are working very well there because they want to work it well. Namely, judges there are expected to push more and more cases to a speedier resolution and if it cannot be resolved by the mechanism of alternatives with resolutions, then it should be adjudicated on and quickly finished. But somehow court processes take much longer here. Even the appointment of more judges is not really going to help us because you have to have competent judges, especially at the higher level. You see, if you have more judges who are incompetent, then the whole system gets badly cluttered up because they pass wrong judgment, which requires to be corrected, and that again goes back. So, it’s a very great conundrum in our country, as to how in one billion people, we have to accommodate a system, which is transparent and which hopefully should deliver something.

HLM: One of the things that has always struck me is that the retirement age of judges is very low.

Nariman: Yes, in fact we have been telling the law minister that the retirement age should really be 68 for the Supreme Court judges and 65 for the High Court judges. But I don’t know if they will do this. At least they should keep the retirement age of the High Court judges at 65 because otherwise it leads also to a lot of wire pulling, as only some judges can come up to the Supreme Court. Those who come up may not necessarily be the best; there are good people that come up but the better people get left out.

HLM: For a country of over one billion plus people, do you feel that we have the Supreme Court of the right size?

Nariman: No, we perhaps require many more, but as I said, more judges. is really not the answer unless we have more judges of superior competence. You see because the idea of a High Court and a Supreme Court, in theory at least, is that the High Court will have superior wisdom and superior materials and equipment’s and the Supreme Court will have supremely wise people who deal with it. But it is not always so, it does not always work out that way.

HLM: Which of the Supreme Court Judges in your imagination has ex-emplified the best of public interest litigation?

Nariman: There have been great judges like Krishna lyer, Chandrachud and Bhagwati; they were all extraordinarily good. Bhagwati was passionately committed and very innovative in his reckoning of the law. But the commitment of one judge is not enough, there has to be a commitment of an institution really.

HLM: In my mind, PILs need to also relate a lot to the human rights part, especially given the constant encroachment from the state and the private vested interests.

Nariman: Yes, there are private interests and apart from that, people have lost confidence in the executive’s motives, motivation. Whenever someone gets their way we believe that he must have bribed his way through, it may not be that way but that is the impression we carry and the corruption that exists there is quite amazing.

HLM: Do you feel that the Supreme Court can still be seen as the final refuge for someone seeking justice?

Nariman: That is the only way it can be, but somehow the executive also lacks in doing things and doing then the right way. For instance, we all say that it is very wrong to torture people but we haven’t [ratified] the Convention against Torture because of some obscure reasons, some bureaucratic tangles; nobody knows why. Most of the civilised world has accepted it. So each government should attempt to accept the United Nations’ various conventions because you can’t go reinventing the wheel, and they are very good conventions, very well thought out; brilliant lawyers have got them in place.

HLM: And we are going backwards in many ways.

Nariman: We are going backwards, but that is a problem of governance.

HLM: Is this a matter of great regret to you?

Nariman: I am very concerned actually about the collapse of the political system at the moment. But the parliamentary system is perhaps the only system consistent with human rights. That is the only system that works quite well, because whenever in this part of the world any other system is tried, it has been a total failure… So we have to take the rough and the smooth.

HLM: That is why the judiciary is so important.

Nariman: Yes, it is the bulwark of democracy and our judges are doing a great deal. There are a few black sheep, but (in general) we must give (the judiciary) credit for what they do because there is commitment, in at least many of them. It is all very well to speak against judicial activism but I’m for judicial activism. There is no other way out, you can’t leave it to politicians or the parliament, they will do nothing.