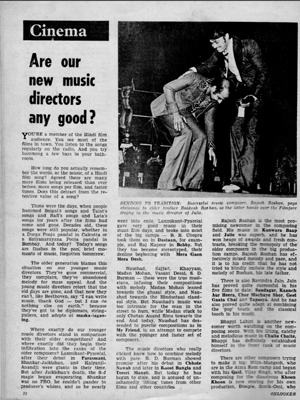

Are our new music directors any good?

Published date: 15th-31st May 1976, Onlooker

View PDFYou’re a member of the Hindi film audience. You see most of the films in town. You listen to the songs regularly on the radio. And you try humming a few bars in your bathroom.

How long do you actually remember the words, or the music, of a Hindi film song? Agreed there are many more films being released than ever before, more songs per film, and faster tunes. Does this detract from the retentive value of a song?

Those were the days, when people hummed Saigal’s songs and Talat’s songs and Rafi’s songs and Lata’s songs for years after the films had come and gone. Decades old, these songs were still popular, whether in a Durga Pooja pandal in Calcutta or a Satyanarayana Pooja pandal in Bombay. And today? Today’s songs are flashes in the pan, brief moments of music, forgotten tomorrow.

The older generation blames this situation on our younger music directors. They’ve gone commercial, they complain, they’ve abandoned melody for mass appeal. And the young music directors retort that the old days are gone, and that now they can’t, like Beethoven, say “I can write music, thank God – but I can do nothing else on earth,” because they’ve got to be diplomats, string- pullers, and adepts at maska-lagao-ing.

Where exactly do our younger music directors stand in comparison with their older competitors? And where exactly did they begin their infiltration into the ranks of the older composers? Laxmikant-Pyarelal, after their debut in Parasmani, Shankar-Jaikishan, and Kalyanji Anand ji were giants in their time. But after Jaikishan’s death, the S-J magic began evaporating. Shankar was no PRO, he couldn’t pander to producer’s whims, and so he nearly went into exile. ‘Laxmikant-Pyarelal gave very good music in their stunt film days, and broke into most of the big camps – B. R. Chopra took them on in Dastaan, for example, and Raj Kapoor in Bobby. But they too became stereotyped, their decline beginning with Mera Gaon Mera Desh.

Naushad, Sajjad, Khayyam, Madan Mohan, Vasant Desai, S. D. Burman – these were the true musicians, infusing their compositions with melody. Madan Mohan leaned towards the ghazal style, and Naushad towards the Hindustani classical style. But Naushad’s music was too intricate for the man in the street to hum, while Madan stuck to only Chetan Anand films towards the end. And today, Naushad has descended to puerile compositions as in My Friend, in an attempt to compete with the younger and faster set of composers.

The music directors who really clicked knew how to combine melody with pace. R. D. Burman showed promise after his debut in Chhote Nawab and later in Bhoot Bangla and Teesri Manzil. But today he has begun to stale, and is accused of unashamedly ‘lifting’ tunes from other films and other countries.

Rajesh Roshan is the most promising newcomer in the composing field. His music in Kunwara Baap and Julie was superb, and he has won heaps of awards and fresh contracts, breaking the monopoly of the older composers in the big production camps. Rajesh Roshan has effectively mixed melody and pace, and it is to his credit that he has not tried to blindly imitate the style and melody of Roshan, his late father.

There is also Ravindra Jain. Jain has proved quite successful in his five films to date: Saudagar, Kaanch Aur Heera, Chor Machaye Shor, Geet Gaata Chal and Tapasya. And he has also proved quite adept at combining the ‘pop’ touch and the classical touch in his music.

Bhappi Lahiri is another new-comer worth watching on the composing scene. With his lilting, catchy and melodious music in Chalte Chalte, Bhappi has definitely established himself in the front rank of music directors.

There are other composers trying to make it big: Nitin-Mangesh, who are in the Atma Ram camp and began with his Qaid. Vijay Singh, who after composing for the disastrous Khoon Khoon is now scoring for his own production, Dimple, Sonik-Omi, who have clicked only with Dil Ne Phir Yaad Kiya and Sawan Bhadon. Shamji Ghanshamji with Dhoti Lota Aur Chowpatty in their bags and Daaku to follow are another new pair. Usha Khanna was good in the beginning, but after she married Sawan Kumar Tak and began composing music for his stunt films, has gone the way the other hackneyed composers have. C. Arjun’s case is one of a literal miracle, for his music in Jai Santoshi Maa was as much a ‘hit’ as the film. However, Arjun is still in the wilderness with regard to fresh contracts.

Hundreds of other aspiring music directors wait in the wings, but unable to convince a producer to give them a try. The producer too is helpless. On the one hand, he will not get good finance if he picks a newcomer to compose music for him. On the other hand, no top-rank playback singer will agree to lend his or her voice to his production if the music is to be scored by a nobody. Tons of Juck, and lots of ‘contacts’- are what are needed for newcomers to come in at all.

There is thus both hope and gloom on the Hindi film music scene – hope because there are people like Roshan and Jain and Lahiri around, and gloom because the days of truly memorable music seems to be past. Perhaps this is because the occidental influence is too strong, and some young directors turn out music that has no Indian roots at all. Only in two films have I been able to sense the impact of purely classical music – Ustad Vilayat Khan’s in Kadambari, and Ustad Bahadur Khan’s in Trisandhya.

Only when our music directors succeed in bringing an absolutely Indian identity to their compositions will Hindi films deserve to be called fully indigenous products. And then perhaps there will be a return of the lyrical music that the previous generation loved so much. People in those days liked music automatically, but now they’re made to like it with excessive exposure to racy tunes wafting out of countless sound service loudspeakers. They get to like it, but they forget it rapidly. On the other hand, old men still recall Saigal and when Shahjehan is shown on television, hundreds of people (mostly young) flock to record shops to buy Saigal’s records to try and recapture some of that old magic.

PROFILE: PROMISING MUSIC DIRECTOR BHAPPI LAHIRI

‘I COMBINE FOLK MUSIC WITH POP’

WHILE I wait for Bhappi Lahiri to make his appearance, his father tells me that Bhappi composed music when he was 16 for a Bengali film called Dadu — and that Lata Mangeshkar and Asha Bhonsle sang for Bhappi in that film. The father is proud of the son’s success — Aparesh Lahiri himself was a music director in Tollygunge, and Bhappi’s mother, Bansari, is an accomplished classical singer.

Bhappi comes in looking very much like a Guru Maharajji. He is short, rotund, wears spectacles, kurta and lungi. I ask him which films he’s composed music for. He turns to his papa, and papa dutifully rattles off the list — Nanha Shikari, Charitra, Bazar Band Karo, Zakhmee, and now Chalte Chalte. Bhappi knew how to play the tabla, Aparesh continues. What with his musical family, his genius is natural, he implies. Bhappi is obviously the reticent type. I begin to wonder whether I’m interviewing the “prodigy” or its creator.

O. P. Ralhan spotted Bhappi at a music programme in Calcutta just after Talash had been released. Ralhan told Bhappi he would wither away in Bengal, that Bombay was the place for him. Bhappi says modestly that his success is due to the pillars supporting him — Ralhan, Tahir Hussain, Lata, and Kishore Kumar. All of them treat him like a son, he adds, and I envy his roster of foster parents.

The Lahiris migrated to Bombay in 1971, and Ralhan immediately signed up Bhappi for Hari Hari Chhaya, which unfortunately is still in the planning stages. But Bhappi has scored the music for Ralhan’s Paapi. He asks me to look forward to the film and the music.

Chalte Chalte was a miracle, Bhappi continues — it sold 50,000 LPs even before the film was released. He likes combining the folk and the western schools of music — he tells me he wants his songs to be melodious and at the same time popular. Mohammed Rafi clicked in that “Nothing is impossible” disco song in Zakhmee, Bhappi points out.

His father feels his “Jalta hai jiya mera bheegi bheegi raaton mein” number in Zakhmee, his “Pyaar mein kabhi kabhi aiso ho jata hai” number in Chalte Chalte, his “Bol sajna” number in Paapi, are conclusive proof of Bhappi’s virtuosity. And then Bhappi chimes in and says he fits the music to the situation — he has used only four instruments for a song in Ratan Mohan’s Sangram, he smiles, and as many as 102 of them in a song in Paapi.

Among music directors, he respects S. D. Burmanda, Madan Mohan and Laxmikant-Pyarelal in that order. Tahir, he says, is another father, but refuses to divulge anything about his music in the former’s forthcoming Aag Ka Dariya.

Bhappi has many more films coming up — Aap Ki Khatir, Sangram, Haiwan, Paapi, Ek Ladki Badnam Si, Aag Ka Dariya. He has given breaks to many new writers and playback singers, he claims: among the lyricists Gohar Kanpuri in Zakhmee, Awadh Khanna in Chalte Chalte, Kulwant Jain in Ek Ladki Badnam Si, Prakash Pankaj in N. P. Singh’s Pyar Mein Sauda Nahin, and Shaily Shailendra in Aap Ki Khatir; among the singers, Dilraj Kaur in S. Kapoor’s Rang De Basanti Chola, Anuradha in Sangram and Aag Ka Dariya, Aarti Mukherjee in Sangram and Preeti Sagar in H. S. Rawail’s Shareefzada.

I’ve run out of questions. Bhappi’s run out of pillars and film titles, Aparesh has run out of cigarettes, and so I decide to leave. Bhappi clasps my hand in both his chubby ones, and invites me to his next recording session.