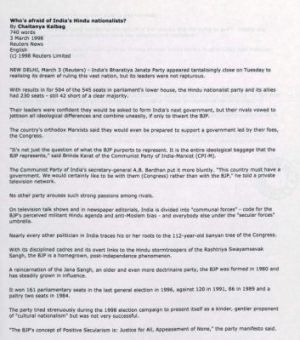

Who’s afraid of India’s Hindu nationalists?

[Reuters]

Published date: 3rd March 1998

View PDF3 March 1998

Reuters News

English

(c) 1998 Reuters Limited

┬Ā

NEW DELHI, March 3 (Reuters) – India’s Bharatiya Janata Party appeared tantalisingly close on Tuesday to realising its dream of ruling this vast nation, but its leaders were not rapturous.

With results in for 504 of the 545 seats in parliament’s lower house, the Hindu nationalist party and its allies had 230 seats – still 42 short of a clear majority.

Their leaders were confident they would be asked to form India’s next government, but their rivals vowed to jettison all ideological differences and combine uneasily, if only to thwart the BJP.

The country’s orthodox Marxists said they would even be prepared to support a government led by their foes, the Congress.

“It’s not just the question of what the BJP purports to represent. It is the entire ideological baggage that the BJP represents,” said Brinda Karat of the Communist Party of India-Marxist (CPI-M).

The Communist Party of India’s secretary-general A.B. Bardhan put it more bluntly. “This country must have a government. We would certainly like to be with them (Congress) rather than with the BJP,” he told a private television network.

No other party arouses such strong passions among rivals.

On television talk shows and in newspaper editorials, India is divided into “communal forces”ŌĆö code for the BJP’s perceived militant Hindu agenda and anti-Muslim bias – and everybody else under the “secular forces” umbrella.

Nearly every other politician in India traces his or her roots to the 112-year-old banyan tree of the Congress.

With its disciplined cadres and its overt links to the Hindu stormtroopers of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, the BJP is a homegrown, post-independence phenomenon.

A reincarnation of the Jana Sangh, an older and even more doctrinaire party, the BJP was formed in 1980 and has steadily grown in influence.

It won 161 parliamentary seats in the last general election in 1996, against 120 in 1991, 86 in 1989 and a paltry two seats in 1984.

The party tried strenuously during the 1998 election campaign to present itself as a kinder, gentler proponent of “cultural nationalism,” but was not very successful.

“The BJP’s concept of Positive Secularism is: Justice for All, Appeasement of None,” the party manifesto said.

It tried to calm fears among India’s 111 million Muslims by promising “equal opportunity and prosperity” and charged that its rivals had “shamelessly pandered to communalism and indulged in “vote-bank politics”.”

But the party unequivocally vowed to build a shrine to the Hindu god Rama at Ayodhya, where Hindu zealots tore down a 16th-century mosque in 1992, triggering India’s worst sectarian riots since the subcontinent was partitioned on Hindu-Muslim┬Ālines into India and Pakistan in 1947.

RSS supremo Rajendra Singh lashed out at the communists in a recent interview with Reuters and said the “communal” label had worn thin.

“It is their way of abusing somebody, calling somebody rightists, capitalists, the stooge of so-and-so … that is the communist way of using a word many times. In many ways the BJP is a swadeshi (nationalist) movement,” he said.

Singh said the Hindutva (Hindu-ness) agenda was harmless.

“The BJP is a nationalist party wedded to the culture of this country and not trying to ape or imitate any paradigms that have been floated in the world like socialism and capitalism.”

The RSS leader said the issue of building Hindu shrines on sites where India’s Mughal rulers built mosques would erase “a national shame”.

“It is a permanent scar on the faith. Millions of people come every year to these spots and they see these temples destroyed and mosques built and they feel very angry,” he said.

He defined the RSS and BJP attitude towards Muslims by saying: “We merely feel that those people who live in India, they may have any religion, but they must follow the culture of this country. They must not feel they are aliens here; they should not feel Arab countries, or Iran or Turkey are somehow nearer to them.”

Whatever the ideological divide, Indian politicians were honest enough to admit that power mattered most in the end.

“This election has not been fought on moral grounds. Morality these days does not exist in politics. Pure mathematical calculations do,” said Kamala Sinha, the junior foreign minister in the outgoing government.

(c) Reuters Limited 1998